Roadmap Your Way to R&D-Product Development Innovation

Intestinal fortitude for innovation is on the decline in most industries. The lackluster economy has made many companies skittish to embrace risk in their product portfolios. How bad has it become? In the 1990s, almost 60% of R&D budgets were allocated to New-To-The-World, New-To-The-Market, and New Product Lines (Robert G. Cooper, Reference Paper #46: Creating Bold Innovation In Mature Markets). Today, that number is below 40%.

Nielsen recently did a study of innovative products (Taddy Hall and Rob Wengel, Nielsen Breakthrough Innovation Report: June 2015). Nielsen examined 3,522 initiatives and identified 12 “Breakthrough Winners.” Ten of the winners were edibles of some type. Other winners included Duracel’s Quantum battery and Paris’ Advanced Haircare from L’Oreal. What happened to all the other categories of products you and I buy? For the time being, the innovation tent has been rolled-up in most industries.

Alas, 30 years of corporate focus on the bottom line has left many companies challenged when it comes to attacking top-line initiatives with confidence (The Journey To Mastering Innovation, Machine Design, November 2015). How will companies overcome the current conundrums of flat to small revenue growth and shrinking profits that have been pervasive for the past few years? Perhaps “roadmaps” might help instill the confidence necessary to once again take on additional risk.

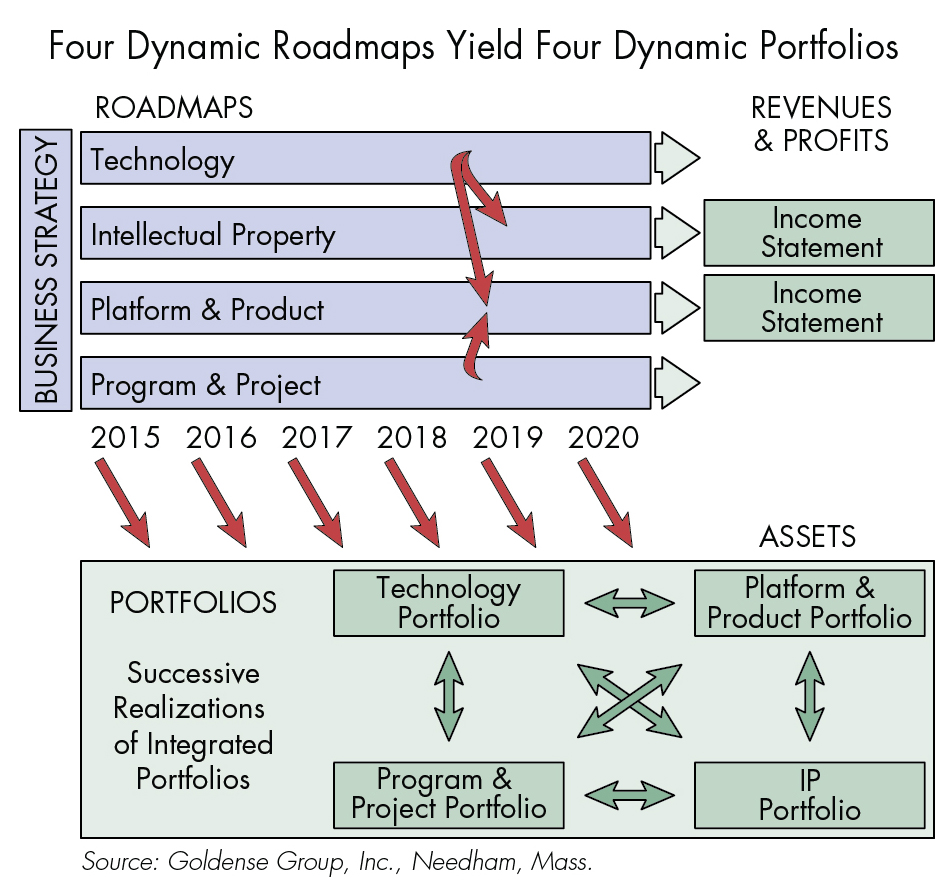

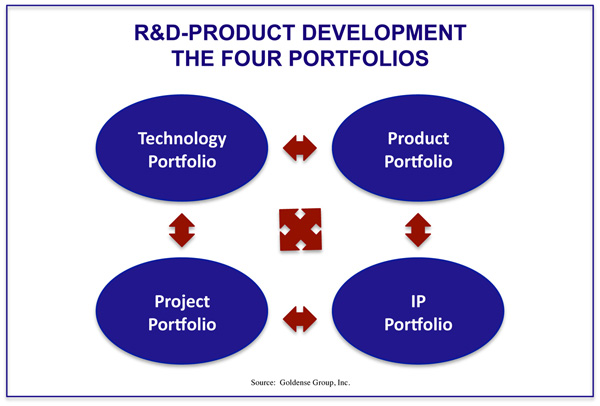

In a recent article, I discussed the need for companies to manage four distinct but integrated portfolios. The best practice is to use four multi-year roadmaps, of the same names, to create those four portfolios.

Roadmap Your Way to R&D-Product Development Innovation [Machine Design – December 2015] discusses how properly managed roadmaps can drive targeted and successive improvements in the four portfolios that most companies manage in this day and age.

Roadmap Your Way to R&D-Product Development Innovation Read More »

![Goldense Group, Inc. [GGI] Logo](https://goldensegroupinc.com/blog/driving-product-development/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/logo-corp-darkBlue-65x65.png)